Greenwood – Abandoned House

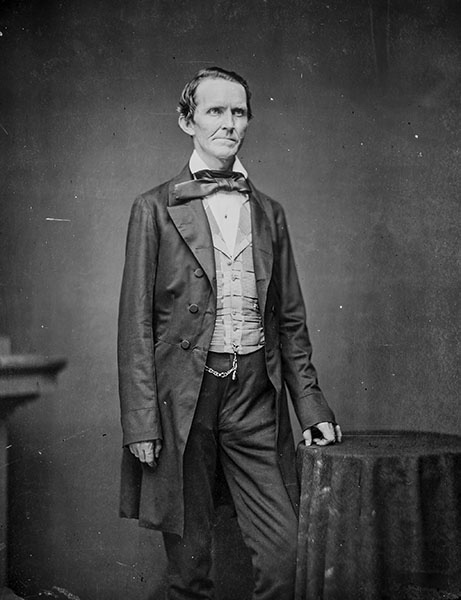

Sydenham Denham Moore was born on May 25, 1817, in Rutherford County, Tennessee. The Moore family moved to Limestone County, Alabama in 1818. Sydenham may have had five siblings. His oldest sister married Edward Asbury O’Neal, a future brigadier general in the Confederate States Army and governor of Alabama (1882-1886). He attended the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa from 1833-1836. Like many upper-class Southerners of the time, Moore was fascinated by the classical traditions of Ancient Greece and Rome. He pursued classical studies in college and eventually studied law. Once he passed the state bar, Moore began practicing law in Greensboro. His interest in the law eventually led him into the judiciary when he became a judge in Greene County in 1840. In 1841, he married Amanda Melvina Hobson, with whom he would have nine children. Sydenham Moore served as a judge until 1846 and later from 1848 to 1850.

After the United States declared war on Mexico in 1846, Moore recruited volunteers from his law office in Eutaw to fight. His recruits made up a unit that came to be known as the “Eutaw Rangers.” Moore’s volunteers boarded a steamboat at Finches Ferry Landing in Greene County and headed for Mobile, before embarking on another steamboat bound for Mexico. The Eutaw Rangers met up with the First Regiment of Alabama Volunteers led by Col. John Coffey and were stationed at Camp Belknap. While at the camp, Moore’s Rangers cared for sick and wounded soldiers, and many eventually succumbed to the disease themselves. An enslaved person, Peter, who accompanied Moore was one of the victims, and Moore lamented his death in a letter to his wife. Peter and the other deceased members of Moore’s unit were buried in northern Mexico.

The Eutaw Rangers stayed at the camp without seeing much combat compared to other units. In March 1847, they were called upon to contribute to Gen. Zachary Taylor’s 20-day siege of Veracruz. The city siege consisted of an amphibious assault and a cannonade bombardment led by Capt. Robert E. Lee. In this conflict, Moore gained military experience that would lead to his commissioning as an officer in the Confederate Army during the Civil War. After returning to Alabama, Moore resumed the practice of law. In the early 1850s, he ran unsuccessfully on at least two occasions for the Fourth Congressional District seat.

In 1855, Moore built a two-story Greek Revival home with four Ionic columns and two-bays windows in Greensboro. Known as Greenwood, the home could be considered two houses in one. When Moore built his home, he incorporated materials from an even older property, Greenwood, built in the 1820s was the plantation home of Alabama’s third governor, Israel Pickens. Although the property has been referred to as the Israel Pickens home, he never lived in the home Moore built and Moore didn’t for very long.

In 1857, Moore represented Alabama’s Fourth Congressional District serving in the U.S. Congress until 1861. He left Congress after Alabama seceded from the Union and joined the Confederate States Army rising to the rank of major. He was killed in 1862 during the Battle for Seven Pines in Virginia. After Moore’s death, Greenwood reportedly passed to the heirs of the Pickens. It was known as the W. C. Pickens House when it was documented by the Historic American Building Survey in 1934 and later as the Greenwood-Sydenham Moore Home when it was listed on the Greensboro Historic District that was established by the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.

Owner C. R. Lawson Jr. gave the state the authority to preserve the integrity of the design of the original exterior of the home, according to the 1980 facade easement. The easement requires the owner to “restore, keep and maintain in a good state of repair the footings, foundation, exterior walls, roof, exterior doors and windows, and to repair, reconstruct, and replace the same as they may be damaged or destroyed by casualty.” The easement put in place by the Alabama Historical Commission also requires the home’s owner to carry fire insurance for at least 70% of its value. The caveat is that if the home is damaged beyond 50% by any cause, “except the willful act of grantors,” the restrictions are not enforceable. The facade easement results in a lower value of the home but the devaluation is somewhat eased by a tax break.

According to the Hale County tax accessor, a deed on the property was recorded in Tom Meymand’s name in February 2000. In March 2002, Greenwood was severely damaged by a fire caused by defective wiring in the back of the home. The home sat exposed to the weather for months awaiting repairs. By December 2002, the Alabama Historical Commission was trying to get the owner to repair the structure, however, the owner wanted to demolish it. The easement put in place years earlier gives the Historical Commission the right to demand Meymand replace the roof and protect the interior that’s been exposed to rain and weather since the fire. Meymand received an insurance payout and decided he did not want to fix the home. He told The Gadsden Times in a phone interview that more than 50% of the home was damaged beyond repair, which relieves him of the legal responsibility to fix it. He indicated it would take hundreds of thousands of dollars to restore the facade.

The commission’s efforts underscore the delicate relationship between private party owners and government agencies intent on preserving pieces of the past. There is little they can do to prevent the deterioration of historic properties unless city ordinances or state laws give them that authority. The Alabama Historical Commission purchased Greenwood from Meymand and repaired the roof and facade. In 2009, the Alabama Historical Commission created a website to solicit offers for purchasing the house. Today, the property remains partially boarded and vacant. There are currently no plans for Greenwood. As of March 2024, the property has been listed for sale for $85,000.

Thank you for reading. Please share the blog with your friends. I appreciate the support.

You can find me on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and TikTok. For more amazing abandoned places from across Alabama, check out my books Abandoned Alabama: Exploring the Heart of Dixie and Abandoned Birmingham.

Source: https://numerologybox.com

Category: Abandoned Place