Huston House at Butler Island Plantation – Abandoned House

Butler Island Plantation was once one of the most extensive plantations in the South. The story of the plantation is a fascinating one, beginning in 1790 when Major Pierce Butler, a Revolutionary War veteran, owned the property. Major Butler was a U.S. Senator from South Carolina and the author of the Constitution’s fugitive slave clause. He owned two plantations in Georgia: one on St. Simon’s Island, where sea-island cotton was grown, and one on Butler Island, where rice was grown. He also owned a mansion in Philadelphia and a country home near the city. In 1812, Major Butler owned 638 slaves and was one of the wealthiest men in the United States. He ran the Butler Island plantation until his death in 1822.

After Major Pierce Butler’s death, his unmarried daughter Frances became a trustee of the Butler Island Plantation, with the overseer, Roswell King, as her co-administrator. Upon the death of Frances in 1836, controlling ownership shifted to Major Butler’s two chosen heirs, John and Pierce, grandsons of Butler’s oldest daughter, who had made their permanent homes in Philadelphia.

Pierce Mease Butler, stood to inherit this fortune (and to become one of the largest slaveholders in the nation) when he met Frances Anne “Fanny” Kemble in 1832. He became infatuated with her after seeing her perform. Butler followed her devotedly while she toured. Fanny fell in love with him, and they were married in 1834 in Philadelphia. Kemble came from one of England’s most prominent family of actors, she took the stage herself to save her family from financial ruin. Though a brilliant actress, the stage was not the true love of Fanny Kemble – her first love was for literature and writing. Throughout her life she would be a prolific and accomplished writer of plays, journals, poetry, letters and memoirs. She had no formal training as an actress, but held audiences spellbound with the sheer force of her personality. She was described as having “masculine” characteristics: she was independent, physically strong, and highly intelligent and she did not hide her talents. In addition to acting and writing, Kemble spoke fluent French, read widely, and was an accomplished musician. In 1832, Fanny set out on two-year theater tour of America, where she was received with great enthusiasm. Audiences were enraptured, and she was soon introduced to political and cultural dignitaries.

In marrying Pierce Butler, Fanny escaped the life of the theater and her family’s precarious finances and entered a life of wealth. At that time, she would later state, she did not know the source of this wealth. The marriage was troubled nearly from the start. Fanny believed that Pierce would continue in his devotion, and Pierce believed that Fanny would curb her independent nature and allow herself to be ruled by him. Differences in opinion on slavery also created friction. Pierce thought he could persuade Fanny of the benefits of slavery; Fanny thought she could persuade Pierce to emancipate his slaves. Early in their marriage Fanny even attempted to publish an antislavery treatise that she had written. Pierce forbid her to do so.

In March 1836, Pierce and his brother John inherited the Georgia plantations. Fanny was opposed to slavery and wanted to see the plantation firsthand, and begged Pierce to take her with him. He refused to do so on his first trip, but finally gave in. Butler hoped the visit would change her views on slavery. Following the resignation of the overseer in 1838, Pierce, Fanny, their two daughters Sarah and Frances, and their Irish nurse Margery O’Brien set out for Butler Island. They traveled for nine days by train, stagecoach, and steamboat before arriving at their destination. Nothing in Fanny’s life had prepared her for this place.

Fanny had been told that the enslaved people were well-treated and never sold. She realized very quickly that this was not true. Working under extreme conditions in a difficult environment, the slaves dug canals and irrigation ditches, built tide gates, and cultivated and harvested rice. Kemble spent four months on Butler and St. Simon’s Islands. During that time, she and Pierce clashed frequently over the issue of slavery. She recorded her experiences in letters which she later compiled and published as her Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation. It is the closest, most detailed look at plantation slavery ever recorded by a white northern abolitionist.

By the time the couple returned to Philadelphia, their marriage was in turmoil. Pierce harassed and ignored Fanny and prevented her from seeing their children. Finally, Fanny gave up her attempts at reconciliation, and left for England. While there, she resumed her life in the theater by performing readings of Shakespeare. She was in the midst of a successful run when she learned that Pierce was suing her for divorce. He contended that she had “willfully, maliciously, and without due cause, deserted him on September 11, 1845.” He filed for divorce on April 7, 1848. Fanny returned to America to defend herself against his charges. After a long and painful court proceeding, the divorce was granted in September 1849. Fanny would be allowed to spend two months every summer with her children, and Pierce would pay her $1500 a year in alimony.

Fanny continued to support herself in the U.S. and in Europe with her highly acclaimed Shakespearian readings. Pierce, however, fell further and further into economic ruin, as he squandered away his vast fortune in gambling and stock market speculation. In 1856, his situation became so severe that the management of his finances was handed over to three trustees. To satisfy his enormous debt, they began by selling the Philadelphia mansion and liquidating other properties, but this was not enough. The trustees turned their attention to the property in Georgia, which consisted of mostly human beings.

In February 1859, the men travelled to Georgia to appraise Pierce Butler’s share of the slaves. Each person was examined and his or her value assessed. This was the preparation for what would be the largest single sale of human beings in United States history. The next month, 436 men, women and children, were sent to what used to be the Ten Broeck Racecourse, two miles outside of Savannah. Some enslaved people were held in buildings used for the stabling of horses. After days of buyers’ inspections, and two days of the agonizing auction, families were separated for the first time in their lives. The Great Slave Auction, also known as the Crying Period, divided families and caused much anguish.

Pierce’s financial situation was saved at the expense of his former slaves. In the meantime, the country hovered on the brink of civil war. In 1861, the war erupted. Again, the family was divided: Fanny Kemble and their daughter Sarah was pro-North; Pierce and their daughter Frances were pro-South. In early 1861, Pierce and Frances went to Georgia. Upon their return to Philadelphia in August, Pierce was arrested for treason; in September he was released. He did not return to Georgia until after the war.

The plantation was abandoned when the American Civil War began. Following the war, Pierce Butler returned to Butler Island with his daughter Frances. He found a number of former slaves living there, and arranged that they would work for him as sharecroppers. Management of the plantation was difficult, and though Frances returned to Philadelphia, Pierce remained on the island despite the dangers of disease. He contracted malaria and died in August 1867.

Following Pierce’s death, Frances returned to Butler Island to continue organizing the plantation, and Fanny Kemble moved to Philadelphia. She continued to perform dramatic readings, traveling, and publishing her journals. Fanny Kemble died in London on January 15, 1893.

Unlike her younger sister Sarah who was aligned with her mother, Frances had adopted her father’s pro-slavery views and kept a diary like her mother. She published Ten Years on a Georgia Plantation in 1883. It is considered the best account of what it was like for whites who were former plantation owners in Georgia during the Reconstruction Era. In Frances’ view, African Americans fared better under slavery than under freedom. Today, the only remaining plantation facilities on Butler Island are the rice mill chimney and the brick kiln, which serve as painful reminders of the property’s past. Due to a lack of slave labor, and the postwar depression in the South, the fifth generation of Butlers sold the remains of their lands in 1923.

Tillinghast L’Hommedieu (T.L.) Huston, nicknamed “Cap,” was born in Buffalo, N.Y. on July 17, 1867. His father, an Irish immigrant, was a civil engineer and his mother was a schoolteacher from Kentucky. His father named him after two great engineers. His early years were spent in Cincinnati before he became an engineer alongside his father on the Louisville and Nashville railroads. When the Spanish-American War broke out in 1898, Huston served in the U.S. Army as a captain of the 16th Regiment of Engineers during the fighting in Cuba. Huston earned the nickname ‘Cap’ during his first Army stint. He remained in Cuba after the war, establishing his fortune by helping the newly liberated country rebuild and improve its infrastructure in Havana. He laid out the streets of the Cuban capital and installed a drainage system for the control of malaria. The Congress of Cuba approved a $10 million contract ($314 million today) for Huston’s company, which was signed into law by José Miguel Gómez, the president of Cuba. His successor, Mario García Menocal, terminated the contract in 1913.

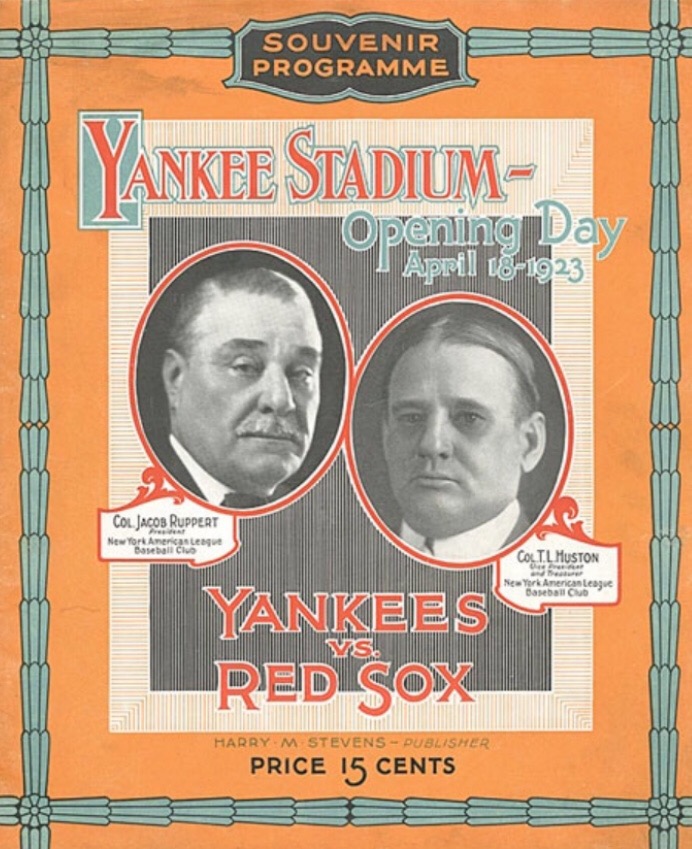

In 1913, Colonel T.L. Huston partnered with Colonel Jacob Ruppert Jr., and purchased the American League Baseball Club of New York. Two years later, they bought a failing Yankees team from Frank Farrell and William Devery, who were responsible for bringing the franchise to New York City. Under Ruppert and Huston’s ownership, the New York Yankees won two pennants, quickly becoming one of America’s favorite baseball teams.

Huston and Ruppert used their wealth to acquire talented players and used the collapse of the Federal League after the 1915 season as an opportunity to acquire them. They reported that they spent $120,000 ($3.4 million today) on player acquisitions in their first year as owners, with the most expensive acquisitions being Home Run Baker, Bob Shawkey, Lee Magee, Dan Tipple, Nick Cullop, and Joe Gedeon. The Yankees finished in fourth place in 1916, their best finish since 1910, and they signed Donovan for another season. In 1917, Huston brought a drill sergeant to spring training to instill discipline in his players, a strategy later adopted by other team owners.

Upon America’s entry into World War I in April 1917, Huston reenlisted in the Army as the commander of the 16th Regiment of Engineers. His regiment sailed for Europe on August 1, 1917, and reached France in March 1918, among the first to reach the front lines. He served in France, building roads and railroads behind British lines near Bethune during the German spring offensive, and then with the American Expeditionary Forces near Varennes and Montfaucon during the Meuse–Argonne offensive. Huston was promoted to major in May 1918, and again to lieutenant colonel in September 1918. General John J. Pershing cited Huston for meritorious service.

As owner of the Yankees, Huston was instrumental in signing and retaining Babe Ruth, at the time, considered “The Deal of the Century.” He also supervised most of the $2 million construction of the original Yankee Stadium completed in 1923. Huston dubbed the stadium as “The House that Ruth Built.” Following a dispute in 1922, T. L. Huston retired and sold his share of the New York Yankees to his partner for $1.25 million, equivalent to a stunning $21 million in today’s money.

After selling his stake in the New York Yankees, Colonel T.L. Huston purchased 650 acres on Champney Island to establish a wild duck preserve in 1923, located south of Darien, Georgia. When Huston learned about the history of rice cultivation on the land, he decided to restore the area. In 1926, he bought the 1,250-acre Butler Island Plantation on Butler Island, a neighboring island, and set about recultivating the land. Huston brought in tractors, dredgers, and thousands of workers to rebuild trenches and levees and plant various species of fruits and vegetables.

Colonel T. L. Huston built the Huston House on the grounds in 1927. The stately three-story timber-framed house includes eleven huge rooms, including many big reception rooms, six bedrooms, and three-and-a-half baths – more than enough space for Huston, his wife and their three children, and the many visitors that stayed there. Over the years, Huston’s home was visited by numerous famous baseball players, including Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb.

In 1929, Col. Huston began planting lettuce, which the plantation continued to produce after his death. Within a decade, Butler Island became one of the largest iceberg lettuce farms on the east coast. Several years later, Huston spent over $100,000 ($1.6 million today) on a herd of Guernsey cattle to establish the plantation as a dairy farm in 1932. The dairy herd assembled by Colonel Huston contained many famous cows with imposing pedigrees, with about 70 total. Excellent pastures near the dairy provided the feed as well as large stocks of silage grown on other parts of the island and stored in the mammoth feed barn and silo. Huston was determined to operate his dairy without spending a cent for cow feed, everything necessary being produced onsite.

The dairy plant consisted of three separate buildings. One, where the cows are fed and watered, is equipped with individual concrete stalls with individual and automatic drinking fountains for each cow. The cows are taken to this barn from the pasture before being milked and are thoroughly washed.

From the barn they go into the milking parlor, first having to pass through a shallow pool of antiseptic solution which thoroughly disinfects their hooves and feet. In the milking parlor they go to individual booths, where they are milked by automatic machines. Only the superintendent of milking is permitted in the building. Before the milking machine is attached to the cows each teat is inspected by milking a small amount into a small satin bag so that its color can be checked. The automatic milking machines take the milk from the cows and deposit it into large, air-tight jars, which are attached to scales which weigh. From these jars it is forced by vacuum pressure through pipes into another building where it goes into the cooling chamber.

From the chamber it flows through into the bottling machine, where it is bottled, securely capped and dated. The bottled milk is then placed in a refrigerated room, ready for delivery to the consumer. While delivery is being made the milk is kept iced until it is at the customer’s door. In addition, the machinery for the actual milking, there are also sterilizing rooms, where bottles and other utensils are thoroughly sterilized under intense dry heat. The pipe connections between the different receptacles that receive the milk are also disconnected and sterilized between each milking.

There was a small ice plant on the property that manufactured 50-pound blocks for use in the milk deliveries, mechanical ice cream churns and churns for manufacturing butter, buttermilk, cottage cheese, etc. Everything is on a semi-automatic basis and is electronically operated throughout.

Locals proclaimed Huston’s Dairy produced the best milk east of the Mississippi. The dairy and plantation became points of interest for many Sea Island visitors in the 1930s. Huston sold ice cream on the roadside and had arranged several milking stalls, where, in the late afternoon, his herd of pure-bred cows were milked by machine, as they stand, stalled and revealed through plate glass. He never advertised his roadside cow-milking show. A local newspaper that mentioned the attraction noted the Coastal Highway was not very wide and only had parking for a few vehicles. However, with its successes came setbacks.

The dairy farm proved to be a challenging endeavor. Huston lost ten valuable thoroughbred cows after they burned to death and a large barn destroyed by fire. The origin of the blaze was never determined.

Still interested in baseball, Col. Huston served as an advisor to the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association during the 1933 season. He arranged for Robinson to join the team as its president. In the mid-1930s, Huston attempted to purchase the Brooklyn Dodgers of the National League, and he stated that his intention was to hire Babe Ruth as his manager. In 1937, he acknowledged his offer to buy the Dodgers for $1.7 million ($34 million today) was turned down.

In March 1938, one of Huston’s cows was adjudged the world’s greatest living milk producer in Class AAA. During a 10-month test, with two milkings a day, the cow produced a total of 13,348.8 pounds of milk and 760.9 pounds of butter fat. Not long after this accomplishment, on March 29, 1938, Colonel Tillinghast L. Huston suffered a heart attack and died instantly while at his desk at home. He was buried at Christ Church in St. Simons, Georgia, on March 31, 1938, with military honors.

Tobacco heir R.J. Reynolds Jr. purchased the estate after Huston’s death. Reynolds was diagnosed with emphysema in 1960 and died four years later in Switzerland. By the 1970s, all operations on Butler Island had ceased.

The Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division currently owns the Butler Island Plantation which is open to the public for picnicking, fishing and bird watching. The house was last used as offices for the Department of Conservancy. It is currently vacant and closed to the public. There are no long-term plans for use or maintenance of the Huston House. Changing climate conditions and recent hurricanes have exposed the house to the elements. In 2019, the Huston House was placed on The Georgia Trust for Historic Preservation’s “Places in Peril” list.

Sadly, on June 26, 2024 at around 7:10 P.M., the historic 97-year-old home burned to the ground. The McIntosh County and Darien volunteer fire departments responded to the scene along with aid from Glynn County Fire and Rescue and the Liberty County Fire Department. The local news reported that the McIntosh County Sheriff’s Office took a man into custody after the fire started.

Deputies apprehended a homeless man named Kyle Gill at the scene and are holding him for investigative purposes, the sheriff’s office told The Darien News. Gill is also being held on a fugitive warrant out of Kentucky. No charges had been filed connected to the fire as of 11 a.m. Thursday. The State Fire Marshal’s office is investigating the cause of the fire.

Thank you for reading. I appreciate your support. Please share the blog with your friends.

Source: https://numerologybox.com

Category: Abandoned Place