Lynnewood Hall – Abandoned House

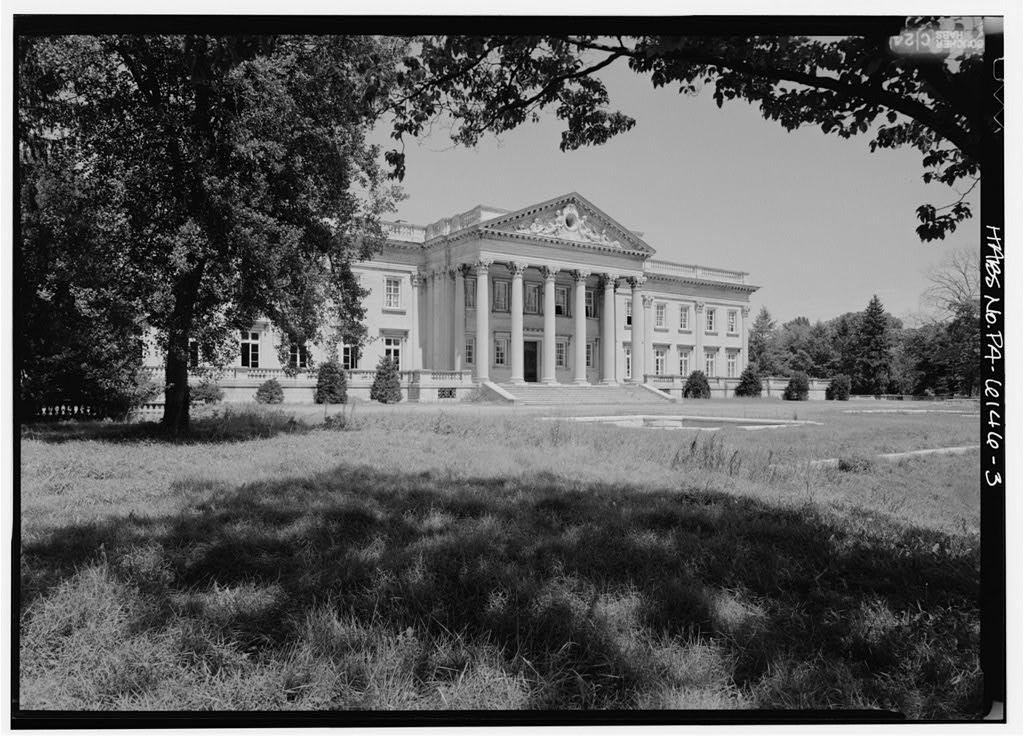

Lynnewood Hall is a spectacular Neoclassical Revival masterpiece and is considered one of the greatest surviving Gilded Age mansions in the United States. The stately home was once one of the finest homes in Pennsylvania, but due to its complex and sad history, the magnificent house now sits shuttered and in a state of disrepair. Lynnewood Hall was built between 1898 and 1900 for streetcar tycoon, prolific art collector, and an investor in the ill-fated Titanic, Peter Arrell Browne Widener. After construction, the mansion stood on a large 480-acre estate in Elkins Park, Pennsylvania.

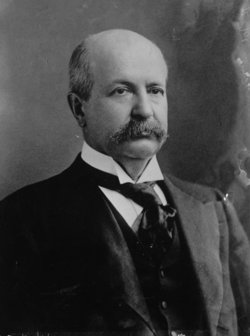

Born on November 13, 1834, to German immigrant parents, Peter Widener was raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As a teenager, he began a butcher apprenticeship and later opened a shop in a local market. The market shop became a social gathering place, and within a short time, Widener was elected Republican leader of the 20th Ward. During the Civil War, the position enabled him to obtain a contract to supply mutton to the Union Army within 10 miles of Philadelphia. Widener earned $50,000 (roughly $850,000 today) from the meat contract. After the Civil War, he invested his earnings in a chain of butcher shops that would become very successful. In 1858, at the age of 24, Peter Widener married Hannah Josephine Dunton Widener, and the couple had three children, Harry (who died in his teens), George, and Joseph.

While in his twenties, Widener became business partners with William L. Elkins. He remained involved in politics, and in 1873, was appointed as city treasurer of Philadelphia. The position was the most lucrative political office in the city since the treasurer accrued all interest from city deposits as spoils of office. Widener noticed a need for public transport and branched out into streetcar railways, horse-drawn commuter cars that would hold a dozen or so people. The streetcars were considered a necessity for those who needed to commute in the growing city. Automobiles would not be available to the masses for several more decades. By 1883, Widener and Elkins had consolidated all the streetcar lines in Philadelphia and later merged with New York operators. The rapidly growing company expanded to Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore, owning over 500 miles of tracks. Peter Widener then diversified into railroads, helped organize U.S. Steel and the American Tobacco Company, and invested heavily into Standard Oil.

In 1887, Elkins and Widener bought a pair of Victorian townhouses across the street from one another. After all, the two were now family since Widener’s oldest son George married Elkins’ daughter Eleanor. Widener’s vast wealth also enabled him to start an art collection of fine paintings and Chinese porcelain. Yet, being filthy rich was certainly no guarantee that tragedies in life were avoidable. Sadly, in 1896, Widener’s wife Hannah died on board the family’s yacht off the coast of Maine. In the throes of mourning, Widener decided to vacate the townhouse. He commissioned renowned architect Horace Trumbauer to design a new home, a place he could showcase his art and somewhere “comfortable” for him and his family. Discussions between the two resulted in Lynnewood Hall, a 70,000-square-foot Neoclassical Revival mansion built of Indiana limestone. Trumbauer took inspiration from two architectural gems: Prior Park in Bath, England, and Ballingarry in New Jersey. When the Widener family moved to Lynnewood Hall in 1900, the estate had a full-time staff of 100 servants that tended to the house and grounds. After he moved, Widener donated the townhome in honor of his late wife to the Free Library of Philadelphia, becoming the H. Josephine Widener Memorial Library.

Across the road from the main house, Widener had a 117-acre farm with chicken houses, stock barns, greenhouses, a half-mile race track with a polo field in the middle, and stables for his thoroughbred horses. In addition to the farm, the property had a power plant, water pumps, laundry, carpentry shop, and bakery, making it virtually self-sustaining. Peter Widener was so concerned about a fire destroying his art collection that he had a hot air heating system installed at the farm and piped the heat approximately 1,500 feet to Lynnewood Hall. Horace Trumbauer also built a carriage house and a gatehouse at Lynnewood Hall. Both houses exhibit similar designs as the main house. The carriage house and stables, later known as Lynnewood Lodge, features elements from the Petite Trianon at Versailles Palace. In 1909-10, Lynnewood Hall went through a renovation; Trumbauer enclosed the swimming pool, added the Van Dyck gallery, and enclosed the east and west porches to create loggias.

Peter Widener decorated his palatial estate with the finest furnishings. He was a fanatic about art and antiquities, a self-taught art collector who, with his son Joseph, amassed an internationally renowned collection. The paintings were displayed in Victorian fashion frame to frame floor to ceiling. Among his many works of art were 14 Rembrandts, including The Mill, which caused an uproar when Widener purchased it for $400,000. The British did not want it to leave England, but Peter outbid Britain’s National Gallery in 1911. The seller was a trustee of the gallery and expected to give the gallery a discount. Nobody would match Widener’s offer. Before being shipped to Philadelphia under protest, it was displayed for two days at the National Gallery. More than 22,000 people came by to get one last look. Peter Widener admitted he overpaid for The Mill but explained to friends it was an investment. The acquisition for that price instantly increased the value of the rest of his Rembrandts.

In the 1920s, Trumbauer returned to Lynnewood Hall to redesign the carriage house to provide living quarters for Joseph Widener’s son, Peter Jr., and his family and named Lynnewood Lodge. Peter A.B. Widener became friends and business partners with J.P. Morgan, working closely together in the steel industry. In 1912, Widener became a 20% stakeholder in the International Mercantile Marine Company, famed for building the RMS Titanic. At that time, Peter Widener was nearly in his eighties and declined the offer to ride on the Titanic’s maiden voyage. Instead, he sent his son George and his grandson Harry. George was the heir of Lynnewood Hall and had followed his father in business and set to take over once Peter stepped down. George Widener, his wife Eleanor, and their son Harry planned to return home on the maiden voyage, following a family vacation in Europe. George hosted several dinner parties aboard the ship in his father’s honor. The lavish event was attended by Captain E.J. Smith, whose death was never officially confirmed and subject to much mystery and speculation. On April 14, 1912, four days into the voyage, the Titanic hit an iceberg. Sadly, both George and Harry lost their lives when the ship sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. Approximately 2,224 people were on board, and more than half lost their lives, making the Titanic one of history’s most devastating marine disasters. Eleanor was lucky enough to survive, boarding one of Titanic’s famously limited lifeboats. After arriving in New York, Eleanor Widener took a private train back to Philadelphia. She devoted herself to charitable work after losing her husband and son to the sea. She would later present Harvard University with the Widener Memorial Library in memory of Harry. In 1931, she donated the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Science building at the Hill School, Pottstown. Her son was a student at both institutions.

On November 6, 1915, after battling a long illness, which some speculated was caused by the grief of losing his oldest son and grandson, Peter A.B. Widener passed away at the age of 80 at Lynnewood Hall. At the time of his death, he was worth over $100 million (equivalent to nearly $2 billion today). His only surviving son, Joseph, inherited Lynnewood Hall. Over the next several decades, the estate would remain central to the Widener family’s activities, remaining in the family even during the Great Depression. Joseph Widener began breeding and racing horses. He shared his father’s love of art and took over the curation of Lynnewood Hall’s renowned art collection. He opened the estate to the public by appointment only between 1915 and 1940. For this reason, the property became known as “the house that art built.” In 1940, Joseph Widener donated the family’s art collection to the National Gallery in Washington, D.C.

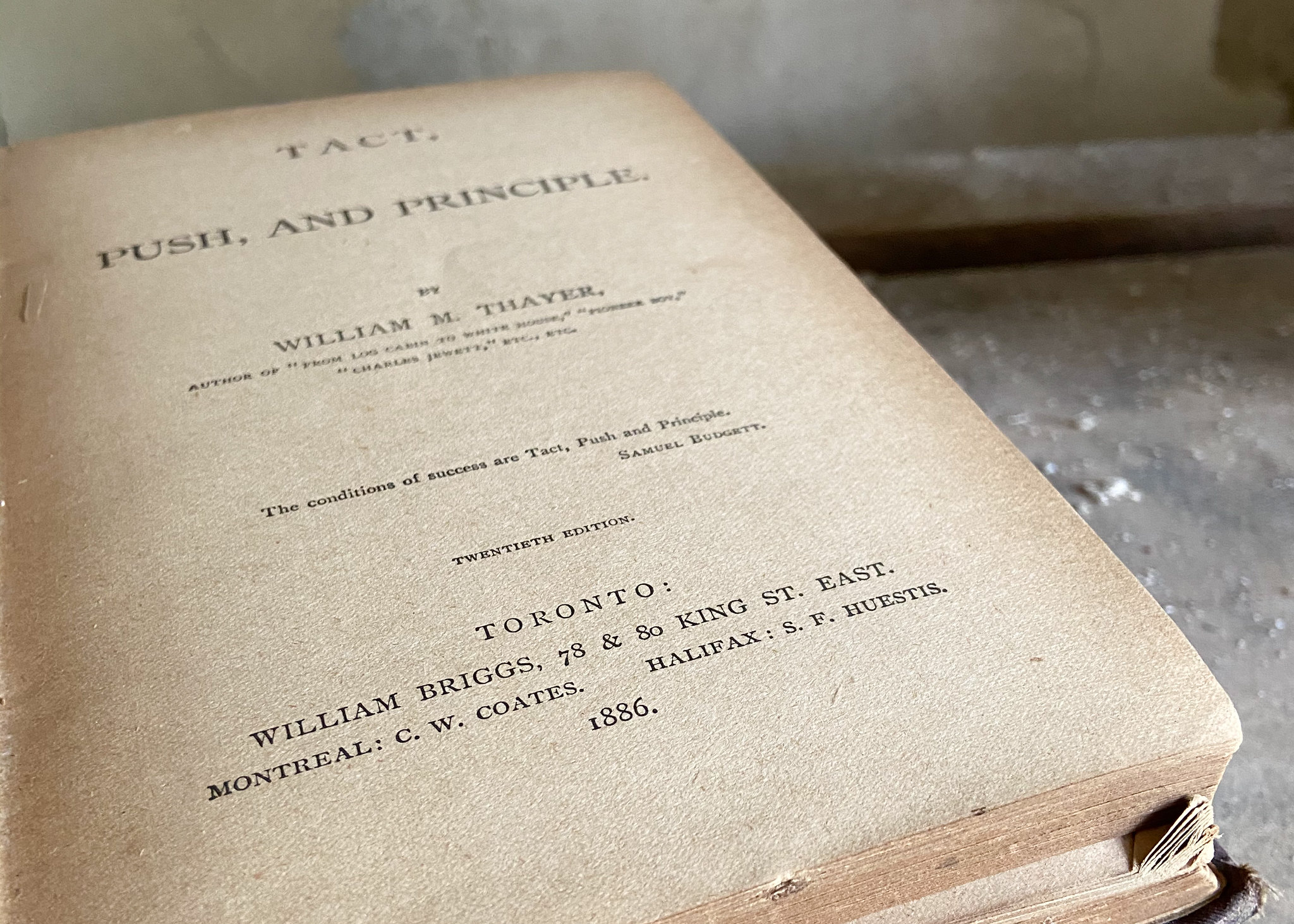

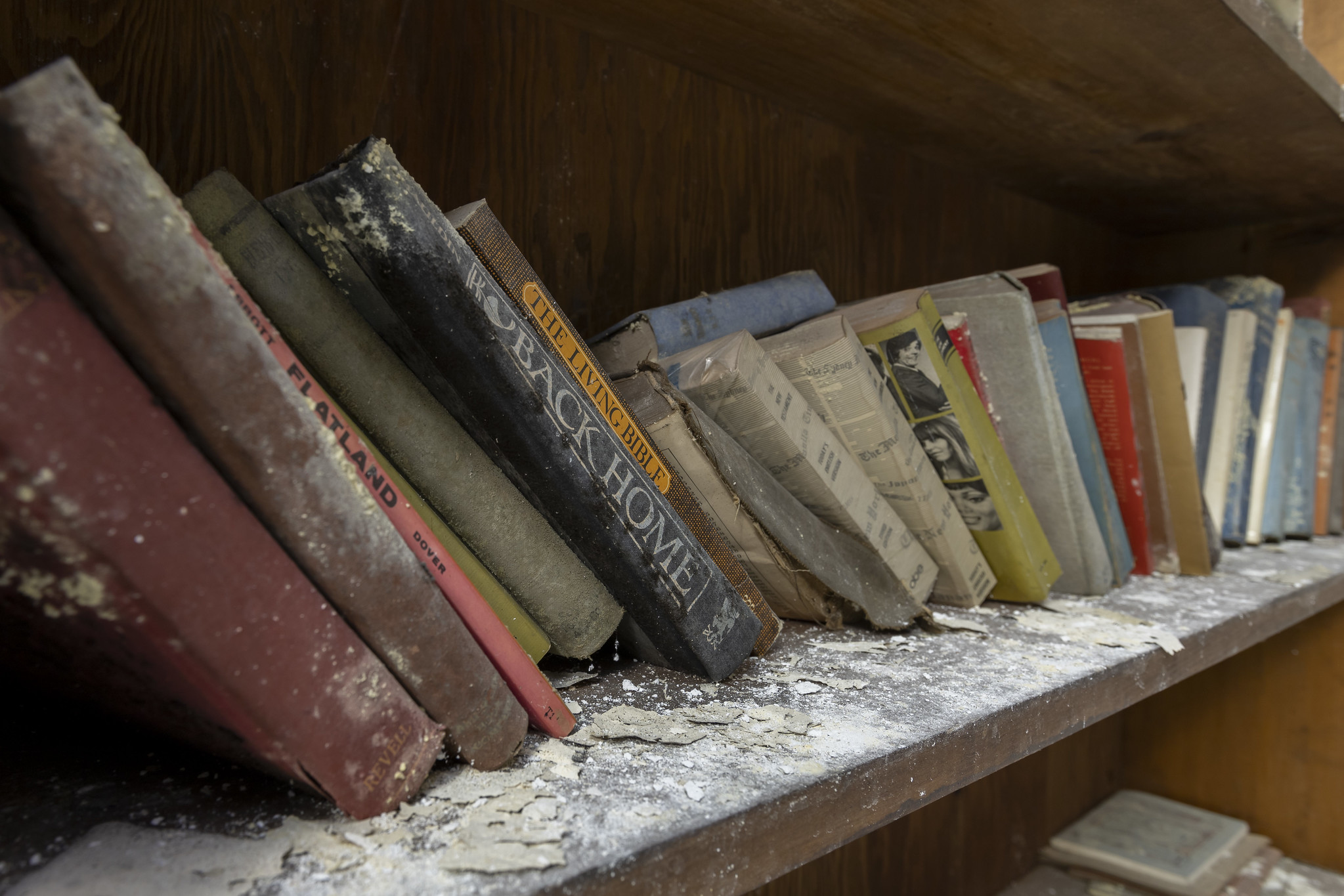

Joseph E. Widener passed away at Lynnewood Hall in 1943. After Joseph’s death, Lynnewood Hall slowly began to decay. His son, Peter A.B. Widener II, remained active in the family businesses, including breeding and racing horses. As a result, the Wideners and their relatives spent less and less time at Lynnewood Hall. In 1944, only a year after Joseph’s death, the contents of Lynnewood Hall were auctioned off. The sale was such an event, it was covered in a 1944 issue of LIFE magazine. For the first time in its history, Lynnewood Hall became vacant, although a caretaker was hired to keep watch over the empty mansion and grounds. The same year, a Philadelphia developer purchased the 220-acre farm from the original estate and built a housing community named Lynnewood Gardens. However, the mansion didn’t sell after years on the market. None of the Wideners or Elkins family wanted it. The same developer purchased it for $130,000 in 1948. He was not able to find a buyer until 1952.

The Reverend Carl McIntire paid $190,000 for the title and another $150,000 to update the electrical system and repair some vandalism damage, according to McIntire’s biographers. He acquired a large amount of surplus paint from the Philadelphia Naval Yard at low cost, and many of the interior walls were painted using this battleship grey paint. McIntire, considered conservative even by evangelical Christian standards, used Lynnewood Hall as a theological school. In 1935, McIntire was removed from the Presbyterian Church after calling their missionaries “too liberal.” He was found guilty of “sowing dissension within the church.” He would go on to form his own Presbyterian Church.

For the next 40 years, Lynnewood Hall would be the home of McIntire’s religious school. He had several hundred students attending at a time. Reverend Carl McIntire was an avowed anti-Communist and spent much of his time during his radio broadcasts working to expose Communists in America during the height of the red scare. Although Lynnewood Hall had full-time residents, McIntire quickly discovered how costly it was to maintain the grounds and the estate. McIntire made his money through contributions from followers, most of which listened to his 30-minute radio show each week. The show aired out of a suburban Philly radio station to more than 600 stations. The FCC shut him down for violation of the “fairness doctrine,” which required radio stations to give equal time to anyone attacked on the air. Religious and civic groups complained about McIntire. According to one clergyman, he used the show to spew his “highly racist, anti-Semitic, anti-Negro, anti-Roman Catholic” views to the world. Not one to be deterred, McIntire, who declared the FCC would have taken Jesus Christ off the air, decided to start his pirate radio broadcast. He purchased a decommissioned navy minesweeper and set out for international waters off the coast of New Jersey. The U.S. Coast Guard quickly put a stop to it. A two-year legal battle between the FCC and McIntire ensued. He lost the case and hundreds of radio stations bailed on him, separating him from the people that donated close to $4 million annually. Carl McIntire’s empire began to crumble.

Under his ownership, many of Lynnewood Hall’s architectural assets – its one-of-a-kind fountain, marble walls, and mantles – were sold off piecemeal to sustain the school’s operations. McIntire was surrounded by people who just wanted money. They auctioned off many of the fine furnishings, took the money, and disappeared. By the 1990s, McIntire’s organization began to dwindle. He lost many supporters, which caused funding to dry up, and the maintenance costs continued to rise. Lynnewood Hall had fallen into disrepair. The slate roof eventually collapsed. There was major water damage and the costs to repair were high. McIntire only used a small section of the building, so the damaged areas were sealed off and ignored. Selling off items did not solve Carl McIntire’s money troubles. He nearly lost Lynnewood Hall several times through a series of loans he took on, including one from a student named Dr. Richard Yoon. In 1993, McIntire was struggling, but still in possession of the property. At a court hearing, McIntire and the Cheltenham Township worked to create an ordinance that would preserve Lynnewood Hall and satisfy the preservation advocates. When the property fell into foreclosure again and a sheriff’s sale was scheduled, preservationists hoped Lynnewood Hall would soon be in their hands. However, Dr. Yoon took over the property in late 1996.

Dr. Richard Yoon was the head of the First Korean Church of New York. He spent a lot of his time fighting local authorities over taxes and zoning, trying to say that Lynnewood Hall was a place of worship and exempt from taxes. The courts disagreed with Yoon and for the last several years the property has been up for sale. It started at $20 million but has slowly trickled down to $11 million in 2019. Today, the mile-long iron fence that surrounds the estate has kept many wondering about the condition of the mansion. The fate of the Gilded Age mansions in Philadelphia’s northern suburbs has often been institutional use or demolition. They become a part of a college campus or religious retreat. Lynnewood Hall has stood the test of time, built of concrete and steel, and continues to hold up against the elements. However, there are doubts about the economic feasibility of restoration. One estimate for renewing the mansion and grounds begins at $40 million. For now, Lynnewood Hall remains in a state of disrepair, teetering on the brink of abandonment.

Since these photos were taken, an advanced security system has been installed at Lynnewood Hall. Anyone attempting to access the property will be arrested. A caretaker lives on the property. No tours are available to the public at this time. For more historic photos, stories, and updates regarding Lynnewood Hall, check out this unofficial Instagram page dedicated to the estate.