Western State Mental Hospital – Abandoned House

The Western Mental Health Institute is a historic insane asylum located in the small town of Bolivar, about 60 miles east of Memphis. The asylum was the last of Tennessee’s three major mental hospitals built in the Victorian era, constructed in 1886-1889, and the only one to remain in operation. The administration building is one of the most significant examples of Gothic Revival institutional architecture remaining in Tennessee. It was the last state mental hospital constructed and habitually the one least funded.

The architects of Western State were Harry Peake McDonald and Kenneth McDonald, brothers who practiced together in Louisville, Kentucky. Harry P. McDonald formed the firm in 1880 with his brothers, Donald and Kenneth. A Confederate veteran from Virginia, Harry graduated with a degree in civil engineering from Washington and Lee University in 1869 before relocating to Louisville in the 1870s. Western State was their first commission in Tennessee. The McDonald Brothers opened a branch office in Memphis in 1887 and won commissions across the state, including the First Cumberland Presbyterian Church (1888) at McKenzie; the Tipton County Courthouse (1890) at Covington; Union Depot (1893) at Memphis; and the Sevier County Courthouse (1895) at Sevierville. The firm had previously designed the Southwestern Lunatic Asylum (1885-1889) in Marion, Virginia. The McDonalds based the design of Western State on the Kirkbride Plan, a standardized method of asylum construction and mental health treatment advocated by Philadelphia psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride.

Unique architectural elements of the Kirkbride asylums include long wings arranged in a staggered, tiered plan so that each connected building had sufficient sunlight and fresh air as well as privacy for the patients and a view of the grounds. Male and female patients were housed in separate wings, separated by a central administrative core with offices, support facilities, and staff apartments. Each wing was subdivided into wards separated by polygonal stair towers. As part of the treatment method, asylums on the Kirkbride Plan were often placed in secluded sites with expansive grounds, landscaped gardens, and farmland that were largely self-sufficient. At Bolivar, the state’s site commissioners selected a rural hilltop farm west of downtown. Construction of the $250,000 four-story facility included rooms for 300-350 patients. Officially opening on November 22, 1889, the asylum accepted 156 patients from an overcrowded Nashville institution.

In 1892, 319 patients were living at the mental hospital. Tennessee’s segregationist policies were manifest at Bolivar in the separate, two-story “Negro Ward” the state built for African American patients in 1895-1896, later expanded in 1913 with a dormitory for African American staff members. In the 1920s and 1930s, the Negro Ward was enlarged with separate buildings for administration, laundry, and receiving patients. In 1948, the original hospital building from 1895-1913 was demolished and replaced with a three-story, mid-century modern building called Luton Hall.

By 1900, the hospital was overcrowded with 594 patients. The system for securing financing for patient care limited the operating budget. In Tennessee, there were three classes of patients: the state-pay patients, the county-pay patients, and the private-pay patients. State agencies agreed to pay for 1 patient out of a population of 1000. Once this portion of the payment had been satisfied, the county was responsible for additional costs. The county payments were consistently behind, and superintendents had to engage in deficit spending to keep the hospital operating. The two most influential superintendents, Dr. Edwin Cocke and Dr. Edwin Levy often faced political pressure from state officials, but both managed to make some improvements in care offered at Western State.

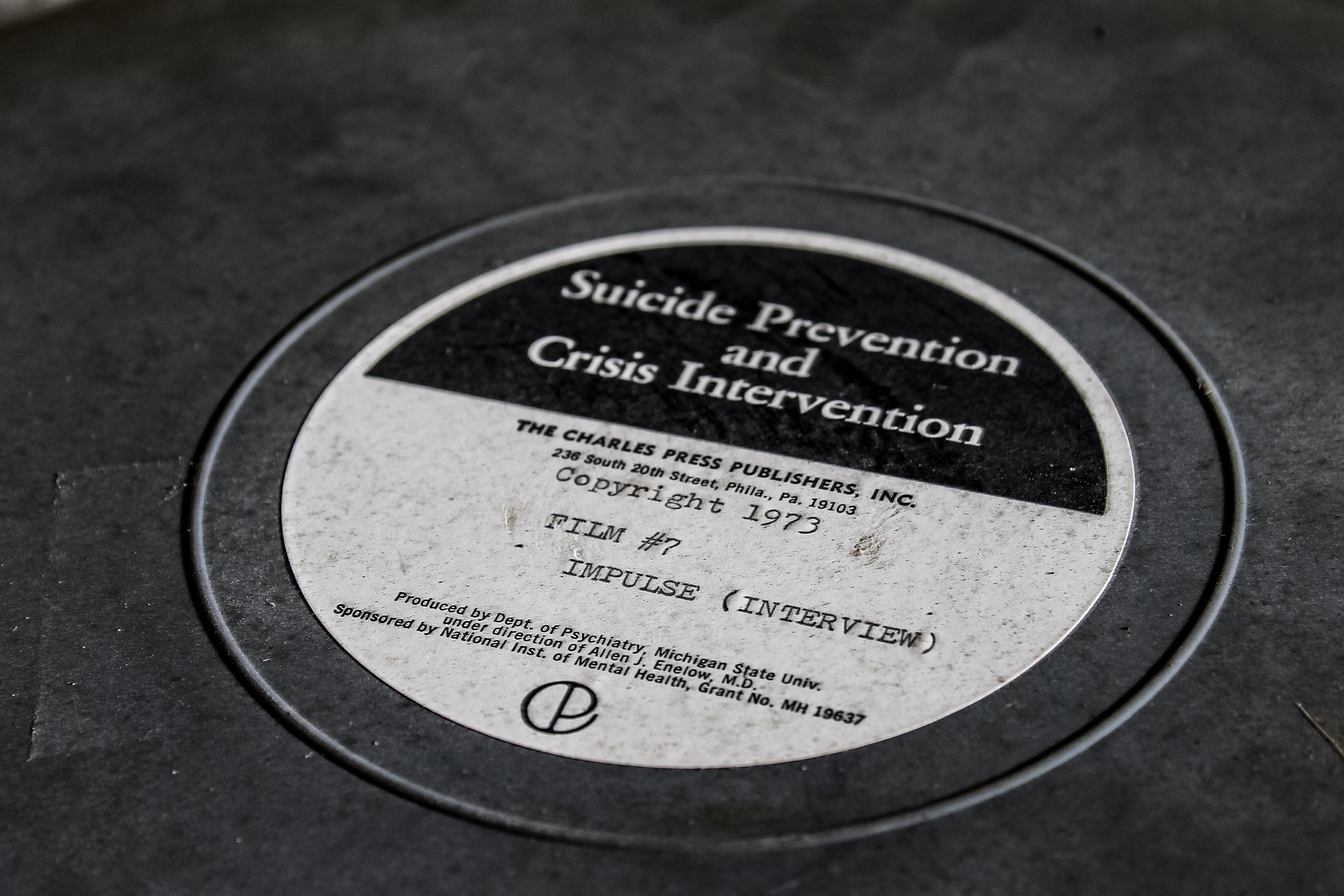

During the 1920s and 1930s, patient therapy tended to be highly eclectic. Patients at Western State received the treatments available in their period of institutionalization. Dr. Edwin W. Cocke began working at the hospital in 1914 as an assistant doctor, eventually becoming a supervisor in 1918. He was the author of a 1919 Tennessee State Law that dealt with the legal aspects of psychiatric treatment and a co-producer of the first diathermy to produce artificial fever treating syphilis of the brain. These new treatments included fever therapy, prefrontal lobotomies, Metrazol injections, and insulin shock therapy, while still relying on occupational therapy.

During Cocke’s tenure, the facility was renamed Western State Hospital, and the hospital received acceptance from the AMA and American College of Surgeons. As a result of this growth, Cocke was responsible for several new buildings, including one for tuberculosis patients, Winston Hall, the Polk Building, the Doctors Apartment Building, a cottage, and the purchase of 235 acres of land. During his tenure, a telephone system was installed, a modern operating room was opened, x-ray equipment was purchased, and the kitchen was modernized. In addition, a dietitian and a dentist were hired. Dr. Cocke served dual roles as the Commissioner of the Department of Institutions and supervisor of Western State from 1933 to 1936, resigning to enter into private practice. Dr. Edwin Cocke served the longest term of any superintendent at the hospital.

The emphasis on treatment was not on care and custody, but on medical and empirical research and experimentation. Many patients were crowded into large dormitories and had little privacy. With a limited number of doctors and attendants and a large patient population, many patients were simply “warehoused.” With the severe staff limitations, patients were fortunate to receive 10 minutes per week with a psychiatrist. As doctors relied on new therapies, the architectural concerns for mental institutions changed. This change is seen in the Polk Building, originally known as the Psychopathic Hospital which opened in 1932. The classically influenced brick building was designed to hold 400 beds. The architect of the Polk Building is Wyatt C. Hedrick, who designed the Sterick Building in Memphis. Although it is a monumental structure, the building does not follow the Kirkbride Plan.

One of the darkest stories about Western State is the institution’s connection to Georgia Tann, who operated the Tennessee Children’s Home Society in Memphis. Tann, with her political connections in the Tennessee General Assembly and the local Shelby County political head, Edmond Crump, and Shelby County Family Court Judge, Camille Kelley, operated a black-market baby adoption agency that became a nationally recognized organization that would later become a national scandal. Tann began at the Mississippi Children’s Home Funding Society around 1920 and initially placed orphans for adoption but quickly realized she could charge hefty adoption fees placing children who had been kidnapped from poor women. In 1924, she started working at the Tennessee Children’s Home Society where she turned part-time baby snatching into a highly profitable business. Tann sold babies to adopting parents throughout America, including movie stars in Hollywood. She charged wealthy clients up to today’s equivalent of $100,000. Actresses Lana Turner and Joan Crawford adopted children through the agency. June Allison and her husband, Dick Powell, also adopted a child from Tann. Professional wrestler Ric Flair, in his autobiography, claimed that he had been illegally taken from his natural mother and sold through the agency to his adoptive parents.

Tann would falsify background records and place children for adoption for as little as $7 in Tennessee. Out-of-state adoptions, which most were, cost upwards of $5000. Tann allegedly made millions from the sale of babies and was chauffeured around in a Packard or Cadillac automobile, dressed in expensive clothes. One of Tann’s sources for children was women at Western State. It is rumored that babies were taken from women in the wards. Young patients were raped and forced to have sex with each other or for money with security guards and local residents. For nearly 30 years, all of the babies that were born at Western State were sent to Georgia Tann’s adoption agency.

Children were sold throughout the United States, Britain, and other countries as underage farmhands. Tann had an established channel for transporting children to England. Reports of the children being enslaved, beaten, or raped by pedophiles were widespread. Unfortunately, Tann’s phony credibility allowed her to be praised in the national press as “the foremost authority on its adoption laws.” Even in 1941, when the Society lost its national endorsement from the Child Welfare League of America because it practiced destroying adoption records, Tann remained in business through her political connections with the Tennessee Legislature.

Children at her Memphis orphanage were starved, beaten, and abused. During four months in 1945, 40-50 children died while in her care, prompting an investigation by authorities. The Tennessee Children’s Home Society was closed in 1950. Georgia Tann died from cancer that same year before the circumstances of the scandal were fully disclosed to the public. An investigation of the Society initiated by Gov. Gordon Browning implicated Judge Camille Kelly and Tann. Kelley was never prosecuted, although she lived a lifestyle well beyond the salary of a Family Court Judicial Officer. However, she did resign shortly after the release of the report. In 1966, Tennessee instituted adoption laws that allowed adopted adults to search any remaining records to locate their parents.

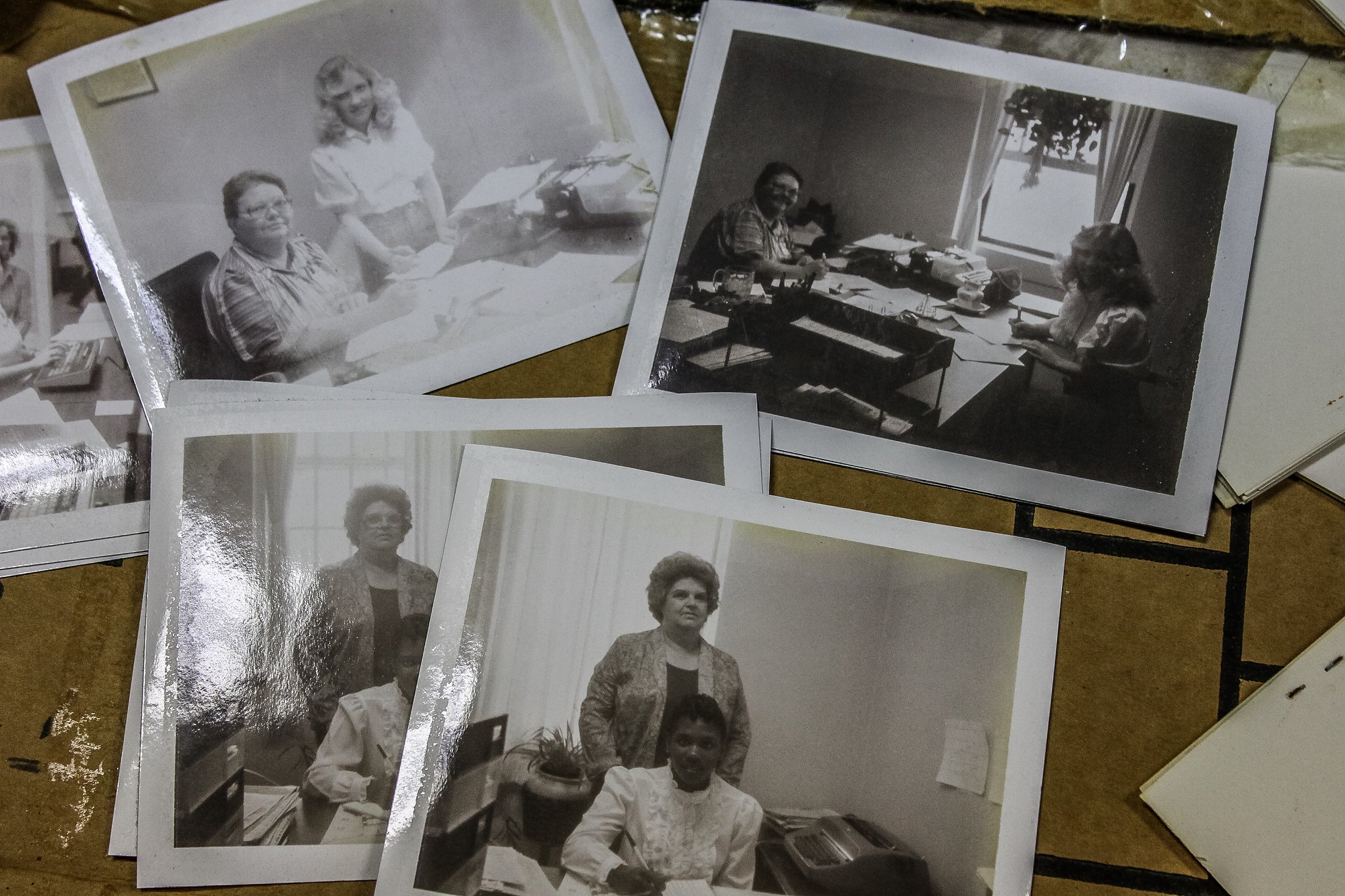

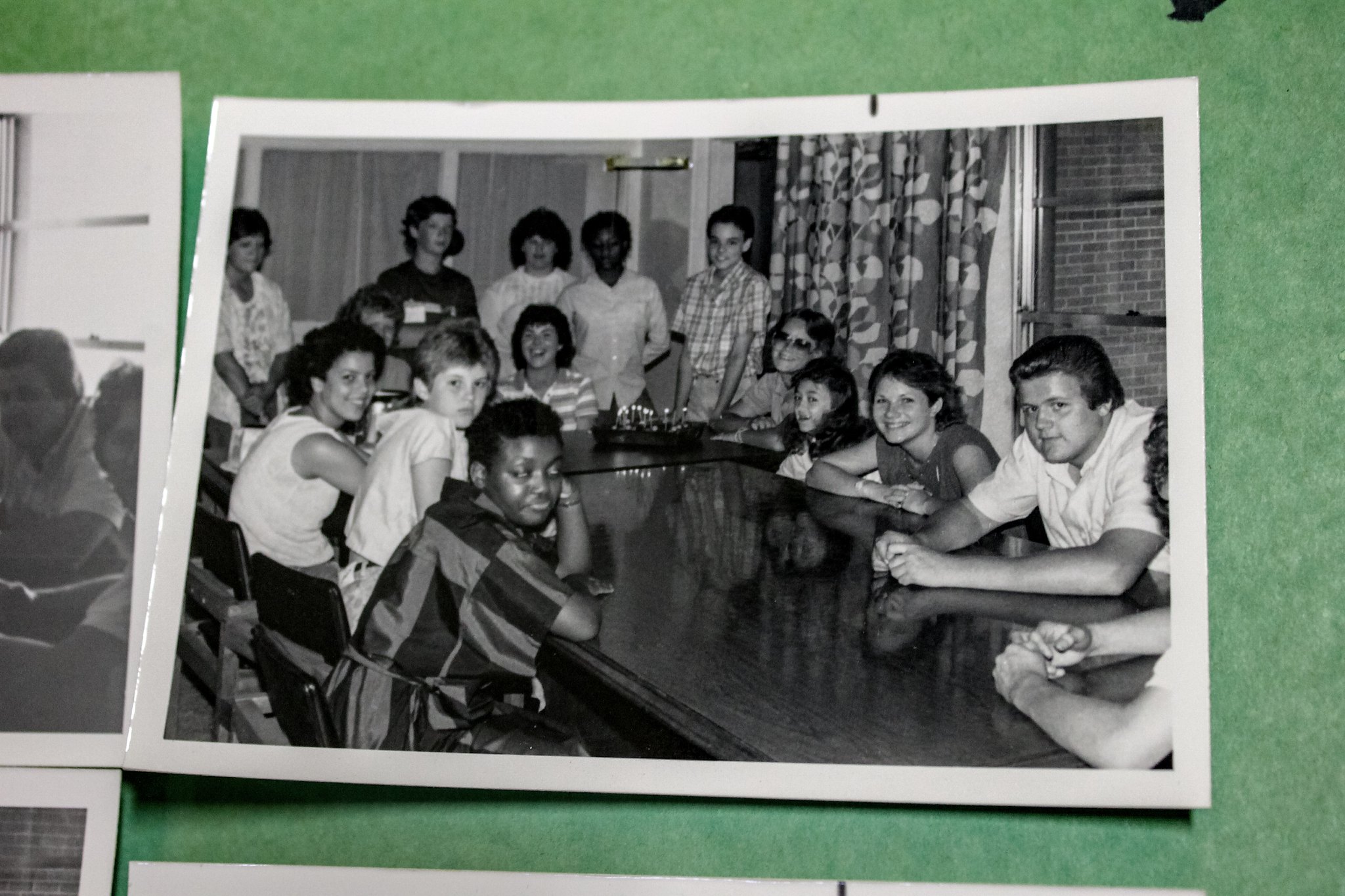

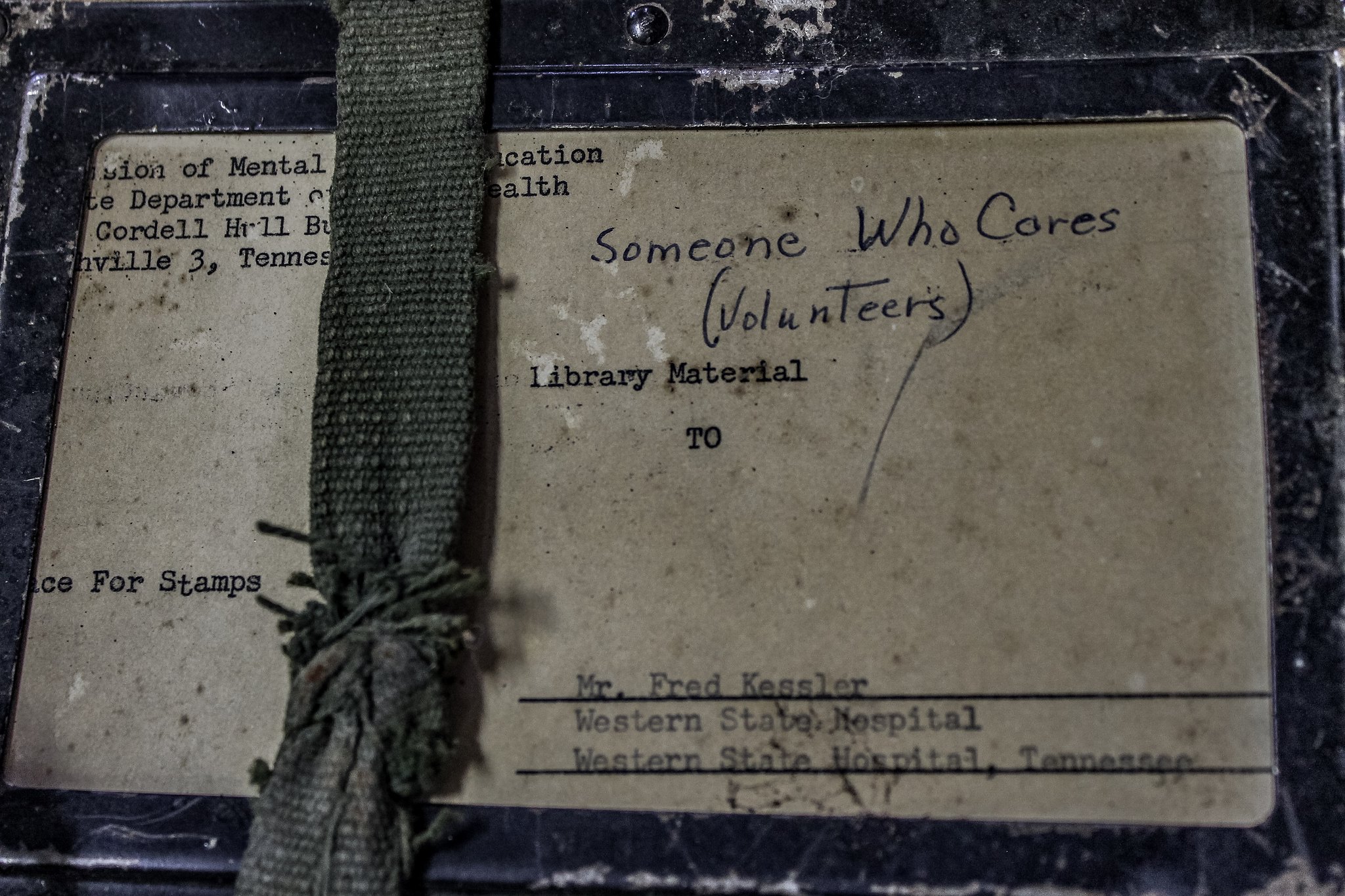

Patients at Western State were free to roam the grounds until the 1980s. It was not uncommon for someone to escape, or simply go missing by walking off the property. Oftentimes, the escapee would be located by security or police and brought back, although, there are instances when people disappeared and were never heard from again. Many of the patients that died at Western State are buried in several cemeteries scattered throughout the campus. Many of the early records of admission and death certificates are said to be long gone. The institution will tell you they destroy records older than 20 years, however, some patient records have been discovered inside the abandoned buildings on the property.

The Gothic Revival administration building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 as part of the Western State Mental Hospital Historic District. The following year, the state demolished the three-story east and west patient wings of the building, leaving only the original four-story central tower and 1927 two-story rear wing. In 2008, the state demolished several other historic buildings, including the 1927 Physicians Apartment Building and two 1920s-era staff houses to construct a modern state-of-the-art $58.5 million psychiatric hospital, which opened in 2010.

The advent of modern psychotropic medications and outlawing unpaid patient labor helped dwindle the overcrowding at Western State. Antidepressants as well as new psychiatric drugs made it more feasible to release people back into the community. Today, Western State serves around 2,500 patients across 24 counties, although only 250-300 of them reside on campus. Many of the historic buildings remain vacant and in disrepair. With a staff of 650 and an annual budget of approximately $35 million, Western State is the largest employer in Hardeman County.

Thank you for reading. I appreciate the support. Please share the blog with your friends.

What to read next:

- Exploring the Enchanting History of Dunalastair Castle in Scotland

- Rowallan Castle: A Timeless Tale of Majesty, History, and Enchantment

- The Abandoned Glass Mansion of Leesburg, Virginia

- Urban explorer discovers abandoned $12 MILLION mansion.

- Bagni Wildbad: The Elegance of the Past Amidst the Italian Alps

Source: https://numerologybox.com

Category: Abandoned Place